Akoya acquired the Phenoptics portfolio in 2018 to provide, in combination with CODEX, a spectrum of powerful tools spanning biomarker discovery to clinical research applications. The story of Phenoptics begins much earlier, however, at Cambridge Research & Instrumentation (CRI). CRI was co-founded by Peter Miller and Cliff Hoyt, and it was where they commercialized the revolutionary multispectral imaging technology. Peter is now VP of Research & Development at Akoya Biosciences, and Cliff is VP of Translational & Scientific Affairs.

We asked Peter to walk us through the path he and Cliff took to bring multispectral imaging to the life sciences. They took a winding road, working with lasers, NASA, and the telecom industry, before focusing their efforts on multiplexed tissue imaging and analysis.

Peter Miller, VP of Research and Development at Akoya Biosciences

Very stable measurements of light

We worked on a bunch of other kind of instruments before we turned to things like Vectra. When you make scientific equipment, you tend to work with leading-edge people. Through the years, we worked with four or five different people who used equipment not at all connected to Phenoptics, who have gone on to become Nobel laureates.

There were two laser control products we made. One was called – it doesn’t matter – let’s call it the laser stabilizer. It was for making a very, very steady amount of laser light. At the time – around 1985 – we were trying to test equipment for measuring exactly how much light the sun was putting out.

And why would you do this? It turns out that the sun gets brighter and dimmer with the sunspot cycle. Every eleven years, or really every twenty-two years, the sun’s poles reverse and there’s an eleven-year cyclical rise and fall in the number of sunspots. This goes back thousands of years, except every now and then it stops.

We were working with Peter Foukal, the third founder of CRI, to test equipment that could go into space and watch the exact amount of brightness and dimness. We were working with folks interested in- get this – whether the sun drove climactic change in the Earth, a topic no one was interested in in 1986. They couldn’t make equipment stable enough to test a measuring tool so that you could believe the measuring tool eleven years later. We made this thing to make incredibly stable lasers. Now you could say: I can build this thing, I can test it, and I can tell you if something’s drifting, it’s the sun, not me.

No one cared. There was just no interest in this at all, because to get anything flying in space requires a lot of infrastructure. The problem was not seen then because global warming wasn’t a big issue. But we had built this thing that made lasers stable.

William Phillips, at NIST, was the first guy doing “laser tweezers”. He had one of our systems, and he used it because the lasers had to be very stable to do the work in the way that they did it. This guy did his first work with the laser tweezers where the lasers are going through our system. We thought, “Oh, this is awesome”.

We wound up working with Bill Moerner, who was at the IBM Almaden California Research Center. I think it was only three or four years ago. He went on to become a Nobel Laureate for his work in single molecule detection. He was using a product we had made, another laser control tool, called a spatial light modulator. It allows you to make, using liquid crystals, a sort of dynamic picket fence. You could turn on and off individual components of an ultra-fast laser in ways to shape it. This turned out to be useful in what he was doing. Again, there was a very small community of people who were interested in this stuff.

There was another guy around this time, named John Hall, who was at JILA at the University of Colorado Boulder. JILA is a joint institute between UC Boulder and NIST. He’s at UC Boulder, and he’s just the nicest guy and a great laser jock. I would see him at some of the photonics trade shows where he’d be walking through. He ran a cool lab and he had built one of these things – a spatial light modulator – himself. He would talk about the way he’d done it. Finally, one year, he went and just bought one of ours and he came back later and said, “I really like yours. It works better than mine.” Nice guy. A few years later he won a Nobel prize for his work in precision spectroscopy.

We wound up discovering that chemists were interested in this stuff. Nobody who was flying satellites into outer space was interested in this stuff. But along the way we had developed ways to make stable measurements of light. This turns out to be essential if you want to get in the business of measuring it precisely.

Soon, we’d gotten some interest from the national standards labs. The NIST facility down in Gaithersburg, two or three national laboratories in Germany, Spain, Poland—probably 10 or so in all. They were using this as part of their primary standards for determining how much light is in a milliwatt of light. Cliff and I did all this junk, which is incredibly involved and elaborate. But it was really just measuring how much light there is and, to be honest, Cliff and I’d had our fill of that, although it was neat.

You could not make a phone call or an internet connection or do any kind of telecommunication without going through some of these things that we made – they’re probably still on the ground.

The dynamic picket fence and the telecom industry

We wound up much more interested in imaging, and the kind of things that tied into Cliff’s interests in biomedicine. But one of the things we had was that picket fence, the spatial light modulator. If you’re a laser spectroscopist looking at ultra-fast lasers, they’re quite useful there. They turned out also to be useful if you’re making telecom equipment, and this was during the telecom bubble of 2000. At that point they were just cutting in, to get more bandwidth or to get more internet traffic. They were routinely deploying 32 and 40-channel communications down each fiber. If you wanted to turn off channel 13, electronically, there weren’t good ways to do it. Maybe you want to switch one out or something that’s broken.

We wound up much more interested in imaging, and the kind of things that tied into Cliff’s interests in biomedicine. But one of the things we had was that picket fence, the spatial light modulator. If you’re a laser spectroscopist looking at ultra-fast lasers, they’re quite useful there. They turned out also to be useful if you’re making telecom equipment, and this was during the telecom bubble of 2000. At that point they were just cutting in, to get more bandwidth or to get more internet traffic. They were routinely deploying 32 and 40-channel communications down each fiber. If you wanted to turn off channel 13, electronically, there weren’t good ways to do it. Maybe you want to switch one out or something that’s broken.

We got a call from some folks at JDS Uniphase (JDSU), which was this giant player during the telecom era. They had put together an apparatus to basically turn on and off individual channels of the ITU – International Telecommunication Union. This was valuable because they were suddenly finding they didn’t have the management mechanisms to send multiple things down the same fiber. They could separate them, but they didn’t have ways to do things dynamically. In the past, if you wanted to do that, they would have someone get in a truck, drive out to wherever it was, or down a manhole cover. They would go to this place and unplug channel 13.

They could see that this was going to get only worse as they started to put more multiplexing, more and more channels. I was flying up every week to go talk with this group and they reported directly to the board of JDSU. We were developing this product, and then around 2000-2001, the bottom completely fell out of the market. There was a giant telecom crash.

They’d tremendously overestimated the need for this stuff. Companies that had been going into this space just cratered all around us. Corning was a big competitor of ours to make these kinds of picket fence devices, and they made a system that had one of these. I remember going in on bended knee to ask if they would consider using us as a supplier of the dynamic picket fence. They said they would think about it. Six months later, I had the chance to buy them for half a million dollars and turned it down. That’s how quickly things were falling apart.

Our product had not yet gotten into production. We weren’t sitting on warehouses of this stuff, and we probably still would’ve gotten creamed, but it turned out that telecom companies were so broke, they would spend on anything that could pay for itself in six months. Our product would allow them to turn on and off channels by pressing a button on a screen instead of getting somebody – who, by the way, would’ve been a union employee – to spend three hours driving somewhere.

The sales of this particular product line, by complete raw luck, were going straight up because it saves money on such a short timescale. It had nothing to do with adding capacity for new customers. It had to do with saving a dime here and there. In the next eight years, we shipped maybe 10,000 of these things. You could not make a phone call or an internet connection or do any kind of telecommunication without going through some of these things that we made – they’re probably still on the ground.

We went through all kinds of reliability, quality, rigorous assessment kind of things. It was very educational. The day we got approved and started to ship them, this guy – who I’d only ever talked to once and was just below the top leadership of JDSU says, “Congratulations, program’s going live. I want you to know how seriously we take this reliability stuff. If we have a problem, I’m not going to call you. I won’t need to. You’ll open the paper the next day, you’ll hear the New York Stock Exchange was shut down by a telecommunication snafu. I’m not going to call you.”

Meanwhile, Peter Foukal, our third co-founder, wanted to go back to focusing on solar astronomy, so we raised the money to buy him out and to do some commercialization towards telecom and the life sciences. Peter is a remarkable person and was a great mentor to me and Cliff. He had a lot of interest in electric fields and magnetic fields in the sun and their effect on total solar luminosity. He wound up part of the International Panel on Climate Change, the IPCC. There are about 50 people in it, and the IPCC as a group was awarded a Nobel prize as well. He went off to focus on that and had an interesting career, while we went off in a more commercial direction and in the life sciences area.

Telecom was a fairly good ride until about 2006 or 2007. But we knew the writing was on the wall. That was all opportunistic from the get-go. We were following our interest and where we thought the longer-term value was, which was life sciences and imaging.

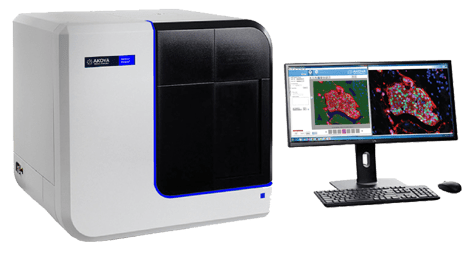

We developed the Nuance…This was a tremendous move forward. It really brought multispectral imaging into consciousness.

Multispectral imaging for tissue

We were very successful, due in large part to being trained by Peter on how to identify sources of research funding and government grants to get your first proof of concept, so that by the time you had something, you were neither in the hole, nor so deeply diluted with venture capital money that you couldn’t do anything with it. Cliff was more active in this than me, but both of us had small business innovation research (SBIR) grants that went through phase two, and Cliff was probably the PI on three or four of those along with a fellow named Richard Levenson.

We had a ridiculous success rate. We were batting something like 90% on grants and proposals being awarded. We were able to do that because we’d come up through our work with Peter, who was on the academic side and very skilled in structuring proposals and going through that process. We were very good at it, and this was vital because the Vectra actually came out of two grants that came from the NIH.

The first thing we thought we were going to do was multispectral imaging of tissue sample. We going to do this with a very fancy illuminator – we had developed something that we called the “SpectraLamp”. We developed this and then realized an automated imaging system for whole slide assessment that uses a Brightfield illuminator is going to miss a lot of the interesting stuff. How about if we try and use liquid crystal tunable filters on that instead? It was, maybe not an afterthought, but it was one of the two design options. The other which was heavily lobbied for was just a very smart, spectrally agile lamp with 40 bands.

We thought, let’s get the versatility. Let’s go with a multi-spectral instrument that uses the tunable filter and go that way instead of just having an agile SpectraLamp. This turns out to have been an extremely good idea. We had our first working SpectraLamp around 2001 or 2002 and we developed the Nuance multispectral camera around 2003. We had to decide which technology we based the automated imager on. Ultimately, we thought, let’s do it as the successor to the Nuance.

We wanted to focus on a systems level. We’d come to learn that if I sell you a tunable filter, then I need to teach you how to integrate that into a camera. I have tremendous support costs, but I only get paid for having sold you a tunable filter. And by the way, you’re going to be unhappy because it’s going to take you six months before you get it to work. I can tell you that before you purchase it, but you won’t believe me. You’ll think you can get it done a in a couple of weeks, but you won’t.

We weren’t happy, and people weren’t happy. That’s why we developed the Nuance. We realized, if we put this thing together, people are going to have to buy a camera anyhow. They won’t mind. Perhaps we can take away their complete flexibility about which camera and just make a fairly good choice for them and integrate it. This was tremendous move forward. It really brought multispectral imaging into consciousness.

The first system we made was in 2005, and the first sale was around 2007 or 2008. That was when we had the grant support to make that automated system. As I recall, we even applied for it with the plan of work based on the SpectraLamp. During the nine to twelve-month review hiatus, we realized that’s the wrong way to do it.

The Vectra product line succeeded the Nuance system

Projects left behind

For those initial products I mentioned, the laser control instruments – we needed liquid crystal cells to make those. We could get those made by third parties, but half the time, they’d be no good because some of these companies weren’t very capable. We decided to start making them ourselves, for the tunable filters. We set up our first foundry to do that back in Cambridge.

We developed the first one there, in a clean room, to make our own cells. Somewhere along the way, I had a grant from NASA to put these things on satellites to look at Earth for environmental sensing. You can determine an awful lot about vegetation and moisture, and all this stuff with visible and near infrared systems using a tunable filter.

There was a guy named Greg Bearman, and he and another fellow, Dr. Tom Chrien, were program sponsors of a couple of grants that I got there. I think Greg’s title was exobiologist or chief exobiologist at the jet propulsion lab. Greg’s another wonderful person, and he began qualifying these photos, which by that time – around ‘95 or ’97 – we were learning how to make them pretty reliably. Cliff had come up with the idea to make them thermally rugged, which was a patented and really essential ingredient to make these things well. Greg started qualifying them for missions to Mars. He was going to put this thing on a Mars Rover and drive around and look with all the spectral knowledge that you can.

Meanwhile, Tom Chrien was looking at putting them in sensors to fly over the Earth as part of the Earth Observing System (EOS). It was a well-intentioned 1980s environmental mission. NASA was going to help us understand earth. The politicians didn’t really want to learn about Earth, so it got slowly defunded. But, the work to Mars continued.

We wound up surviving the equivalent of a Cassini rocket launch. It was 50 Gs or something ridiculous and being frozen to liquid nitrogen, surviving extended radiation and outer space. We were qualifying these tunable filters to go to Mars.

Somewhere around this point, I think in 2000, NASA had terrible luck with rockets destined for Mars blowing up on the launchpad there. Two or three of them in a row. Everybody who was in queue to have their thing fly to Mars on the next one has to take a step back. Everyone’s lost their place in line by two or three of these things. Of course, they also had to stop and have a period of self-reflection on why this was happening.

After the third one blew up, people thought, “Okay, I’m going to go do something else. If I’m ambitious and my interests are of this type, it’s not going to happen by going to Mars.” Greg was one of them. We never actually got built into anything that would fly to Mars, but we did wind up with tunable filters. I think there’s two of them still in the International Space Station. Japan has made, I believe, the smallest imaging satellite ever launched. It’s about the size of a beach ball and it’s basically a camera, a tunable filter, a lens, and some telemetry gear.

We did get into space, but we didn’t get into deep space because of all that. But Greg Bearman is interesting. He was an imaging wizard and a Jewish guy, and he was very interested in Judaica and the ancient Judaica. I remember him coming out with a bunch of pot shards from 300, 400 years ago to look at them and make some spectral measurements using tunable filters. He wound up doing work where these tunable filters were used to image the Dead Sea Scrolls. I remember being called by somebody from the BBC – they were going to make a documentary about this. I don’t know whether they ever did.

The Dead Sea Scrolls were, as I remember, found just after World War II, and they’d been in some cave that adjoins the ocean. It had been often wet and dry and wet and dry, and they were caked in all this crud. When they were found, the first question was, what are they? The next was, are they authentic and old? And then, how are we going to make any sense of them? Because they’re all covered in this crud. They ended up using multispectral imaging to distinguish superficial dark black-colored crud from 4,000 or 5,000-year-old ink underneath it, because they’re not the same in infrared. The FBI built a few forensic systems on the same premise. I can tell that you forged this check or changed the amount, because the ink looks like the same blue, but in the infrared it’s not – there are subtle, spectral differences.

There was one project which was to image the Sistine Chapel. It underwent a tremendous renovation. I think it took about two years, for the ceiling where Michelangelo’s frescoes were. Before they touched anything, they wanted every possible way of recording the state of this thing, both for posterity, and in case anything happens. Somebody went up there with this imaging station, which we’d helped them put together. They were up on scaffolding six feet from the surface, taking pictures through the visible in the near infrared. I did ask, “Can I come with?” It was a no.

These are all the things we left behind when we decided to focus on life science. They were pretty cool, but we realized we couldn’t pursue all these neat forensic uses or all these other different things, because we were going to vaporize. It was with some regret because some of these things were awesome. We really wrestled with it.

Nobody was talking about what you could do as a young, scientifically curious person while you plotted out your next steps.

Where it all began

The very first project Cliff and I worked on together was with Peter Foukal at the company that the three of us left to go form CRI. It was a company called Atmospheric and Environmental Research (AER). The project was to do analysis on a Commodore PET computer. It was the work that actually led to the precise measuring system for looking at the sun. We had to build what we called a cryogenic radiometer. I had recruited Cliff to come join Peter Foukal. We had both gone to Williams College a couple of years apart. We sort of knew another a little bit then. Our friendship now of – I don’t want to say how many years – is almost entirely post that time

I had been brought out by Williams College to be at one of those career days. There was nobody else coming back to talk about cool things you could do in the sciences if you were a technical person wanting to do something before you went back to graduate school. Everybody was there to say, “Come work for this bank for three years before you get your MBA”. Nobody was talking about what you could do as a young, scientifically curious person while you plotted out your next steps.

Cliff was that guy. That’s how we connected. I was, at that point, heading off to graduate school, so it was kind of like transferring. I maintained one day a week, where I would come back from Dartmouth, where I was in grad school, to Boston to kind of check in and work with him. Through the years, we’ve gotten a lot out of recognizing that we have complementary ways of looking at things. I will miss things that Cliff will get and vice versa. We didn’t know that at the time. That was not part of the interview process, but that’s where it started.